The fig tree metaphor and the fear of being irrelevant: a self-fulfilling prophecy

It's no news that all girls in their 20s relate to Sylvia Plath's fig tree metaphor. Still, I can't think of anything else as I rot in bed, aimlessly scroll through reels and think about death.

Like every twenty-something-year-old girl who spends too much time worrying about things she can’t control—while doing nothing about the things she could control—at night, I stay awake thinking about Sylvia Plath's fig tree metaphor.

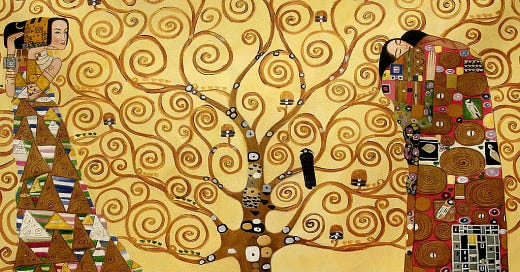

I stare at my ceiling, where the darkness of the night is sporadically broken by the lights of the double-decker buses passing by in the street outside. And there, on that dark canvas, I can almost see it. Golden knobby branches, the bark marked by pencil-drawn swirlings, with lush leaves blossoming from silver gems. A Klimt painting. From each branch, hang dozens of ripe, succulent figs.

Esther, the protagonist of Sylvia Plath's The Bell Jar, sits before the same mirage. She gazes at the fruits, and through Plath's expert pen, she writes: “One fig was a husband and a happy home and children, and another fig was a famous poet and another fig was a brilliant professor, and another fig was Ee Gee, the amazing editor, and another fig was Europe and Africa and South America, and another fig was Constantin and Socrates and Attila and a pack of other lovers with queer names and offbeat professions, and another fig was an Olympic lady crew champion, and beyond and above these figs were many more figs I couldn't quite make out. I saw myself sitting in the crotch of this fig tree, starving to death, just because I couldn't make up my mind which of the figs I would choose. I wanted each and every one of them, but choosing one meant losing all the rest, and, as I sat there, unable to decide, the figs began to wrinkle and go black, and, one by one, they plopped to the ground at my feet.”

There’s something about this metaphor that strikes deeply all girls my age. The same way all girls my age cry when they hear Vienna by Billy Joel. "Slow down, you crazy child," Joel whispers in my ear, "You’re so ambitious for a juvenile."

Every night, the fig tree watches down on me from the dark ceiling of my room, as I desperately beg my brain to fall asleep. But perhaps it’s the hours I spent endlessly scrolling on Instagram, or the screen’s blue lights that burnt into my retinas. Or my body, restless, because I’ve done nothing but rot in bed all day, and my limbs, fingers, and brain seem to beg me to give them something to do. Some kind of stimulus. The very purpose for which they were created.

Since I was little, I was instilled with the idea that I was destined for great things. My parents, my teachers, everyone seemed convinced that there was something special about me. Part of it was perhaps the fact that studying and being good at school had always come more easily to me than to my peers. Maybe it was because I was quiet, docile, compliant, and this is the kind of woman society rewards and showers with positive reinforcement. Or perhaps it was because I’d always had a special inclination toward words. Looking back, I can’t say whether my love for writing was something I created myself or something that was instilled in me. Perhaps what I always really loved, even more than the written words on a blank page, was being told how good I was.

Anyway. The other day, I was in a classroom during an introductory creative writing lesson, and - for the first time in my life - I was on the teacher's side. In front of me sat a dozen children, tiny, so small that I could barely believe they could actually read. The teacher (the real one, whom I was supposed to assist) asked these little humans what writing meant to them. One of them stood up and began to describe how, for him, writing was a thick, viscous liquid that pushed from within, eager to come out and flow openly. And I was left speechless. I, who didn't even know how to spell the word "viscous" in English.

The fact is, for me, writing has always been the opposite. Not something alive, liquid, flowing, where you just have to turn on the tap and let it out. In my application for the creative writing course at the University of Birmingham, almost five years ago, I described writing as a powerful weapon. An unsheathed sword, sharp, sparkling, and encrusted with diamonds. A divine blade I could barely hold between my weak fingers. A tool I only wished I could learn to wield.

Four years have passed, and since then, the hilt of the sword has become familiar, tight against my palm. I wield it masterfully, lift it and spin it above my head, brandishing it in front of anyone willing to watch just because I can. Because I know someone will be entranced. Someone. Not me. I, who lie in bed at night, staring at an imaginary fig tree.

Now, I won’t go on with lavish metaphors just to sweeten the awareness with which I find myself writing this essay, in the middle of the night, when I should be sleeping because tomorrow I start my master’s degree and I haven’t even prepared the material for the first seminar yet. The point is that Sylvia Plath’s Esther Greenwood was stuck in stasis, unable to choose a dream or a goal, and therefore let all those possibilities wither before her eyes. And I know that I, too, am partly guilty of the same practice. I constantly fill sleepless nights and new notebooks with dreams, projects, and plans, and then, when it comes to transferring them from the page to real life, I let myself fall back onto the bed. I crawl under the covers, open TikTok. Because it’s easier that way.

Easier than what? What am I so afraid of, that I’d rather let my body and mind decay in a perpetual state of inactivity on the mattress than try all those things I know I want to do with my life?

The answer lies in the fact that I did, at some point, reach out. I let my fingers touch the skin of the figs hanging above my head. But then, as I gathered courage and plucked it from its stem, the fruit withered in my hands. Like a reverse King Midas. Everything I touch dies, inexorably, before my eyes.

And I know it’s a matter of perspective. I mean. When I look at myself from the outside, floating above my own head like a ghost, I can almost see an accomplished young woman. A girl who published her first book at eighteen. Who graduated with top marks from one of England's most prestigious creative writing courses, in her second language. One who found a boy who loves her madly. One who published a second book at twenty-two, with one of Italy’s leading publishers.

So why do the figs seem to be rotting, in my eyes?

Because for everything I do, I could do it better. For every success, there’s someone doing more. Someone achieving results I couldn’t even dream of. There’s another author who, at my age, has already published four books and travels around Italy welcomed by fans cheering her name. There’s a twelve-year-old who already wields that mystical sword that took me years to learn to balance. And there’s a voice in the back of my head that sighs and rolls its eyes. If I can't be the best at everything I do, what’s the point of even trying?

So I end up not doing. I don’t write for fear that people who now love me will eventually forget me, and I’ll forever remain the author who peaked at twenty-two with a silly romcom. I don’t go running in the morning for fear that my body will betray me and give out before it’s deemed acceptable. All the dreams, projects and plans for the future fill notebook after notebook. Each one gets scribbled for ten pages and then abandoned in a pile under the weight of those that will come after. And they’re all doomed to dust. Because a person with brilliant ideas is a genius. A person who tries to actualise them and fails, is a failure. As long as the figs hang on the tree, withering and falling on their own, I have nothing to be held accountable for. But if they wither because I picked them, then the responsibility falls on me.

Sometimes I wish I was born a simpler creature. How I wish mundane things could make me happy. I wish that the love of a man, a house to call my own, a job that pays the bills, and children to take to soccer or dance practice, could be enough. Instead, I seem unable to settle for anything less than excellence. But since excellence is an abstract concept known perhaps to no one, then I, consequently, am doomed to unhappiness.

Maybe that’s why I so often find myself thinking about death.

Many times during the day I stop, in the middle of whatever I’m doing, and I’m overwhelmed by the awareness that I could die at that very moment. The bus I’m on could crash. My heart could give out. Someone could step out of an alley and stab me, just to snatch the brass necklace hanging from my neck that’s worth next to nothing. I could die right now, as I’m writing these words. My computer could catch fire and burn me alive. First melting the skin of my thighs on which it rests. Then igniting the sheets that wrap around me. And all that’d be left of me would be a pile of half-scribbled notebooks and a hundred books I never read.

I don't know if it’s this thought that freezes me and keeps me from taking control over my life, or if it’s the awareness that – deep down – a dark part of me is reassured by the idea.

Like every night, I will close my eyes fearing I won't wake up tomorrow morning. Once that thought passes, I'll think that tomorrow will be different. I could get up early, go for a run, write a thousand words, prepare for my seminar, have breakfast, put on makeup, get dressed, make my bed.

Like every morning, tomorrow I will open my eyes, turn off the alarm, and roll to the other side.

I love you and your writing, you always put into words exactly how I feel